Macro Blog Apr-21

The Post-Covid Consumer: Bounce-back Britain

The recession experienced in the UK over the last year has been like no other for two principal reasons. Firstly, as a function of government-enforced ‘lockdowns’ this has been a ‘deliberate’ recession – it did not come about due to traditional economic cyclicality – and, also, a co-ordinated one as countries around the world formulated similar policy responses to the emergence of the pandemic. Secondly, and partly in recognition of the first point, governments across the globe, including in the UK, have provided unprecedented levels of fiscal support for businesses and workers in the form of furlough schemes and various business tax relief and loan mechanisms. The fiscal support was also partially a function of the relative absence of ammunition in the monetary arsenal as the pandemic struck, at least in terms of traditional policy responses. At the beginning of the Global Financial Crisis, Bank Rate was 5¾% providing some scope to provide stimulus via rate cuts. At the start of 2020, the prevailing rate was just ¾%.

As the UK emerges tentatively from lockdown and with the country’s impressively efficient vaccination programme offering the hope of a permanent release, it is worth considering the shape of consumers’ finances and confidence levels to provide guidance on the likely recovery trajectory for the economy. Our analysis strongly indicates that consumers will emerge from the pandemic and ensuing lockdown in a far stronger position than might have been expected given the severity of the recession, and with considerably enhanced financial firepower with which to catalyse a broader economic recovery.

Periods of economic contraction, even mild ones compared to the experience of 2020-21, almost always result in an increased level of saving activity amongst consumers – partly as spending habits are reined in (either as a precautionary measure or as a direct function of curtailed income) and partly as providers of credit become more circumspect.

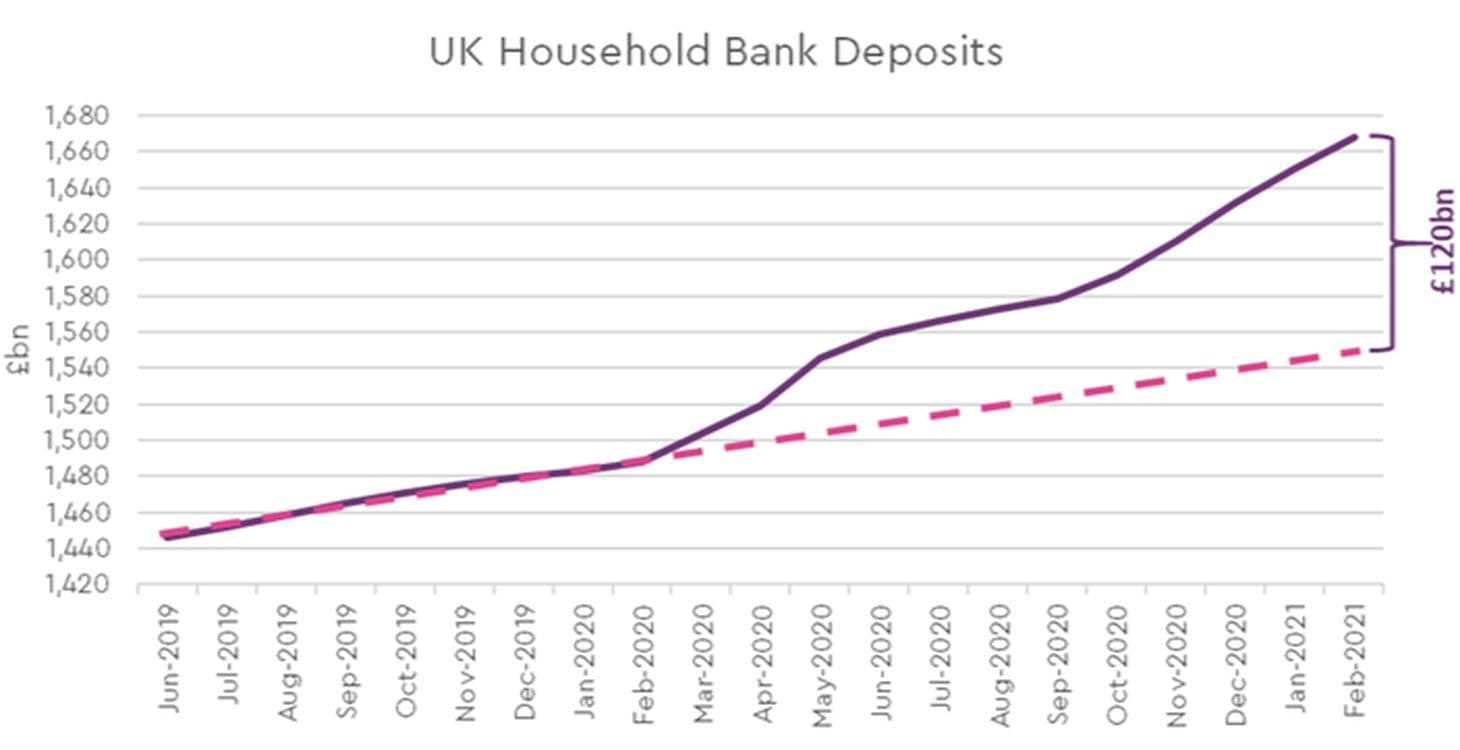

In the past year, there has been a massive increase in saving by UK consumers with cyclical, voluntary saving augmented by involuntary saving as the opportunity to spend on things such as transport, gym memberships, pubs and restaurants has been curtailed. The net result is that UK bank accounts are much fuller than might have been expected emerging from a significant recession – relative to trend, around £120bn more cash is on deposit in household bank accounts. For context, this equates broadly to the size of the UK grocery market or, put another way, an average of £5k per household.

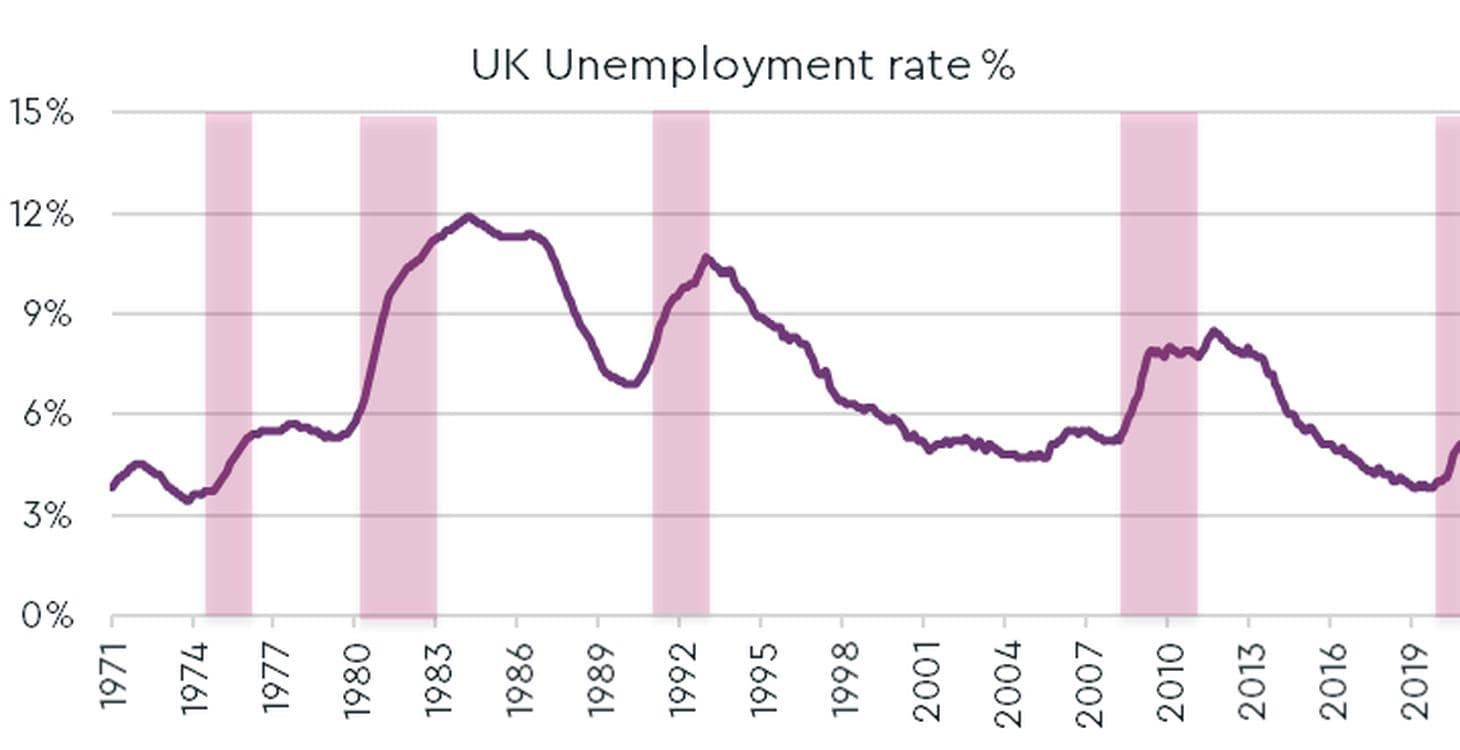

There is also strengthening evidence that the labour market ‘defence’ policies – in essence aimed at minimising ‘scarring’ to the economy – have proved effective. There are currently c4m workers on furlough, down from almost 9m at the peak in Q2 last year and while unemployment has started to track higher the peak is now expected to be reached at 6.5%, far lower than was initially forecast and notably lower than the peaks experienced in previous downturns (9% in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, over 10% in the early 1990s recession and 12% in 1984). Not every job will return, of course, however it is notable that in the period since the Global Financial Crisis, the UK economy did prove to be remarkably adept at creating jobs. Moreover, those sectors which were hardest hit by the pandemic (for example retail and hospitality) tend to be those which are most flexible from a labour perspective (and hence able to bounce back quickly) and are, in many cases, likely to be beneficiaries of considerable pent-up demand.

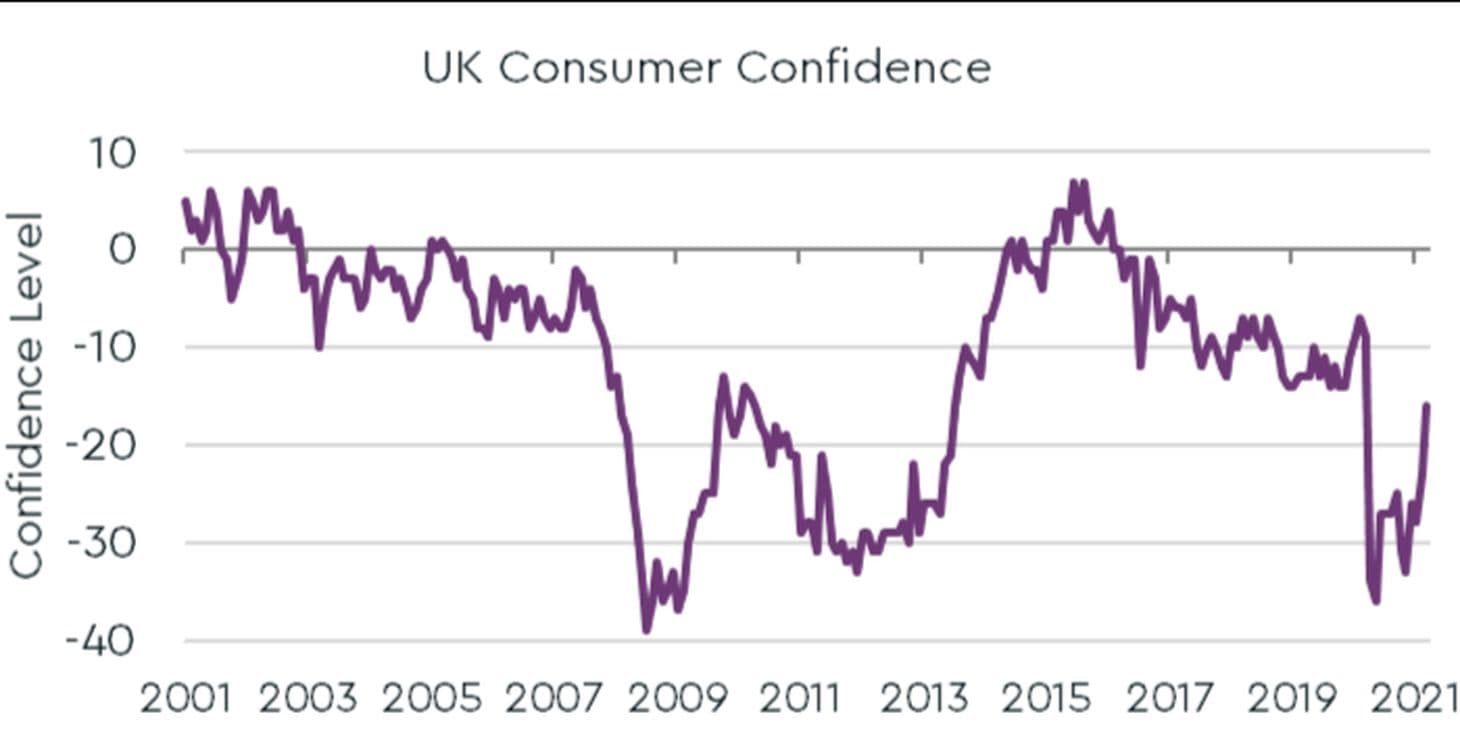

Taken together, the accumulation of significant savings and a labour market which has been successfully defended from the worst ravages of a fierce downturn, the conditions undoubtedly exist for a period of supernormal spending. We would not expect all £120bn of the excess cash horde to be spent in the coming months – consumer confidence, though well above the trough reached in May last year remains substantially below a level which could be described as ‘buoyant’, hence a degree of caution is likely to be exercised. Nonetheless we do expect the next 6-9 months, assuming that the exit from lockdown proceeds as currently planned, will be characterised by strong levels of spending.

This recovery period is undoubtedly very positive for the trajectory of the economy coming out of recession - c70% of GDP relates to consumer spending, after all, hence a consumer-driven recovery will carry significant power. It will not, though, apply evenly across spending categories. Some areas, including most notably hospitality (pubs, bars and restaurants), will likely see a sustained surge in customers as substantial pent-up demand is unleashed. The quantum of the ‘excess cash’ supply also suggests that ‘big ticket’ categories (furniture, cars, large electricals, home and garden) will be beneficiaries. Leisure, meanwhile, looks set to be a mixed picture – holidays (restrictions allowing) could perform well, while cinemas and gyms may have been more sustainably impaired by changes in consumers’ habits during the past year. In retail, the re-opening of stores will inevitably lead to a moderation in online spending growth rates although we expect the penetration of the online channel to have experienced a positive quantum leap through the pandemic and beyond.

At True we invest at the intersection of consumer behavioural change and technological development and so disaggregating cyclical and structural forces, differentiating between the temporarily buoyant from the sustainably growing businesses, will require careful diligence. However, in aggregate, a recovering economy experiencing accelerated channel shift and technological adoption provides an exciting background in which to deploy capital productively. Meanwhile we are highly encouraged to see, first-hand via our Partnerships with the likes of Primark, M&S, TJX, Morrisons and others, a definitive increase in the appetite amongst corporates to invest in digital and technological innovation. Reigniting growth in productivity is a structural challenge for the UK economy which can only be overcome by investment (in education, skills and technology) – the best hope for success is that the private sector, starting with the scale incumbents of today and augmented by a wave of disruptive innovators, embraces this challenge.